Andrew Pepper [1]

Nottingham, UK

Note: References in this on-line version are included within square brackets [ ] and are listed at the bottom of the page. It is also possible to click here to open a new window containing the full list .

ABSTRACT

Many artists, scientists, designers, architects and members of the general public have craved for large-scale holography since the 1940's. It seems ideally suited to architectural, design and environmental projects and many attempts have been made during the last 50 years.

Some of the early, pioneering, uses of holography in architecture, design and large-scale art environments are highlighted here, with details of large commissioned works as well as other solutions to the problem of size and scale. Will the medium ever live up to the expectations we place on it?

INTRODUCTION

The announcement of a new technological discovery, or invention, invariably brings with it an expectation of greatness. The nature of the discovery, the fact that it is announced into a world which did not previously know about it, and the inherent ‘promise’ involved artificially inflate expectations. If the discovery is of interest to a broader public audience (by this I mean people ‘outside’ the confined professional practice which has borne this new discovery), then expectations can become even more inflated, unbridled by the anchoring knowledge of the expert in that field. In general, holography was one of those discoveries, in particular the suggestion that it might ‘one day’ be used to create large-scale three-dimensional images ‘floating’ in our world, fanned the fires of expectation. Although we might have expected a roaring furnace, which could keep us warm for decades of possibilities, we have experienced only ‘sparks’.

The following will highlight some of those sparks and show, I hope, that even a tiny glimmer of brightness (a small idea executed well) can generate ‘heat’, which might be the basis for the giant furnace we all hope for. We might not, realistically, expect a raging furnace, but neither is it a pyre.

GABOR

When Dennis Gabor announced his discovery of holography during 1948 in Nature [2] , the implications were massive, although there was a long ‘incubation’ period while the technology caught up with the theory. Gabor realised the potential of his invention and made several predictions for it, including, in a 1970 interview, the possibility for large- scale, panoramic, holograms: "I expect such panoramic holograms to become even more important as a new medium of art than for three-dimensional architectural "renderings" and the like"[3]. Thirty years on from these comments we are still waiting, but progress has been made and there are now many examples which show the potential of the medium, and technical process, which make it possible.

FUELLING THE FIRE

During the late 1970’s, holography exhibitions began to take an excited public by storm and fuel the media ‘feeding frenzy’ which often accompanies this type of phenomenon.

In the catalogue to the first Light Fantastic Exhibition, held at the Royal Academy of Art, London, in 1977 [4], the excitement of this very successful show was reflected not only in the press reports but the catalogue itself. Here we find a description of a holographic auditorium proposed by Anton Furst, where the audience can experience state-of-the-art projections, including holographic images, while being ‘transported’ around the auditorium on an hydraulic platform.

It was, unfortunately, never realised but this type of project and the inspiration which accompanies it have helped shape our view of holography’s potential.

It is not a difficult leap from Furst’s idea for a holographic auditorium to the ‘HoloDeck’ made famous in the Star Trek TV series and films. This ‘manifestation’, although possible only because of TV and film special effects, does highlight a significant problem in the ‘public’ view and expectation of holography. We have seen the HoloDeck, so it is little surprise that when visitors to holography exhibitions view the ‘relatively’ small images there (compared to the giants of science-fiction myth), disappointment sets in. That said, many of the elements of what we wish for are in place. Tiny parts of the jigsaw have been shaped and the potential of some of those pieces will be highlighted in this paper.

VISUAL BIAS

This paper has a personal bias. It is not a definitive document on the development of holography, architecture and design, but a ‘snapshot’ of some of the more recent objects, installations and events which have taken place over the last 10-12 years. The bias is directed towards work produced by artists which tend to receive little detailed documentation.

The terms architecture and design are used here very broadly, not only to encompass structural building projects but also large-scale art installation works which deal with the notion of ‘placement’. The use of holography for decorative effect, which may be neither ‘art’ nor ‘design’, is also included as it makes up a significant area in the public use of visual holography.

PREVIOUS DISCUSSION

In 1994 the article "Beyond the Gallery Ghetto" [5], although primarily about how holography had moved out of dedicated galleries and museums into more open areas of display, did deal with several artists and projects working with concepts of scale, public- sited art and how this related to building and exhibition structures. Artists discussed were: Sam Moree, Margaret Benyon, Rick Silberman, Melissa Crenshaw, James Gaywood, Setsuko Ishii, Douglas Tyler, Dieter Jung, Doris Vila, Sally Weber and Graham Tunnadine. Some of them have produced new works which will be discussed here, along side newcomers to the medium of holography. Sam Moree will present details about his own work at this conference[6]. Further information about artists working primarily with holography and glass (glass being a constituent element of many architectural projects) can be found in "Windows with Memories, Creative Holography in the Real World"[7]. Jo Fairfax, one of the artists featured in this article, is also presenting an expanded discussion of his work at this conference[8].

DOCUMENTATION AND VISUALISATION

Perhaps one of the most obvious uses for holography in an architectural environment is the recording of models used to pre-visualise new buildings. Architects, planners and developers produce detailed models of their structures as a method of showing how the finished building, or complex, might appear to clients and backers. These models can be costly and are often fragile, so a logical step has been to use holography as a high definition method of three-dimensional recording. This can either provide an attractive alternative to the traditional model, in sales presentations and corporate meetings, or can be a practical method of transporting the 3-D image of the original model to different locations.

Although there are many examples of this type of ‘architectural’ holography, one which has an interesting ‘double life’ is a piece by artist Martin Richardson. His 2 x 1 meter hologram for 552 Kings Chelsea Limited was used in a successful exhibition in London, to help promote a new building development, but is now to be on display at the Museum of London, where it can be seen in the Contemporary London Gallery, opening summer 2002. What originally began life as a detailed recording of an architect’s model has become a museum display in its own right[9], reflecting the changing face of modern London. It is also some indication of how attractive holographic images are in this sort of display environment. Would the museum designers have considered showing the original physical model, or does the holographic version have more ‘visitor appeal’?

Another hologram, produced by John Perry of Holographics North[10], Vermont, USA, in 1987, also became an attraction in its own right and remained on display for several years – well into the nineties. As Perry explains: "The purpose of the hologram was to show their visitors how the museum would look after the renovations were done, and do it in a futuristic, dreamlike way."[11] It is clear that holography adds something ‘extra’ to the process of ‘documentation’ which sets it apart from the more ‘traditional’ physical model.

The holographic process is not, however, confined to the Hi-fidelity, 3-D of models which already exist. Designs produced using computer visualisation systems can be output to holography as a method for showing how a structure might appear in ‘real’ three dimensions, as opposed to ‘graphic’ space. A considerable amount of work has been undertaken in this area at the MIT Media Lab’s Spatial Imaging Group[12].

INCREASING THE SCALE

One of the greatest drawbacks of the holographic process has been the relatively small size of the plates used to record them. Large-sized works on meter square glass plate and film did help to alleviate this perceived problem, but even works on this scale were ‘lost’ in architectural environments. Placing several smaller holographic ‘tiles’ together to contribute to a larger ‘whole’ has been a standard solution. Lack of scale can be further compensated for by ‘spreading out’ these ‘tiles’ via supporting constructions, which are either there to frame and display, or as an integral architectural element.

Many artists have produced large installations for galleries and festivals which, although not truly architectural in concept, do demonstrate how spaces can be transformed using holographic elements. Doris Vila has worked with large holograms, computer-controlled lighting, video and computer projections to create almost ‘submersive’ light environments[13], Harriet Casdin-Silver installed several large holographic portraits with audio ‘domes’ in front of them so that comments from the sitters could be heard while standing in front of their portrait[14]. Philip Boissonett has incorporated holograms in large metal ‘globe’ structures which use interactive sensors to change the lighting of the constituent holograms. Marie-Christiane Mathieu mounted holograms onto the upper sections of large glass plates which ‘lean’ against the gallery and become structures in themselves, rather than simply ‘frames’[15]. This list is by no means exhaustive and the use of holography combined with other media and materials is growing in popularity.

PLASTIC LIGHT

Embossed holography, apart from offering an economical mass-produced material for packaging, promotional printing and novelty items, has given artists and designers a new material to work with which would allow large areas of holographic pattern to be used in buildings and sculpture. Artist Sally Weber[16] has used this material in several large-scale projects to great effect.

The holographic ‘fish scales’ in "Flight of Fish", produced in 1990, make absolute sense here in this outdoor fountain. Each of the 50 fish is on a pivot so, as the direction of the wind changes, these weather vanes swivel, catching sunlight and diffracting rainbow colours around the pool.

Artist Melissa Crenshaw also used embossed holographic material to cover the interior of the Canadian Pavilion for Expo ’92 in Seville, Spain[17], in collaboration with Vancouver Architect Bing Thom [18].

This, now celebrated, example of how extremely large areas of holographic material can be incorporated into an interior structure, demonstrates ways in which artists and architects can incorporate specially constructed materials. Here the embossed holography sheets were laminated between glass so that water cascades down over the holographic surface and further diffracts the light shining on it. In recent years Crenshaw has been carrying out research which has resulted in diffractive elements for use in interior, lighting design and glass structures[19] .

TILING

The plastic materials used for embossed holography are often not appropriate for interior design or architectural environments due to being delicate and requiring post-production to encapsulate them into a more robust surface (often glass). Several companies have now produced finished materials, which incorporate holographic elements in stock ‘tiles’.

The use of these holographic tiles has become a useful source of decorative material for interior design and the production of cladding for larger structures. Joel Berman Glass Studios, Vancouver, Canada[20], for example, offer a range of glass textures and surfaces. Their Tactile™ Wall product includes holographic and luminescent textures which designers can specify.

Here the pastel, subdued, effect, so often a by-product of indirectly illuminated diffraction gratings is used as the backdrop for Brasserie 8-1/2, a bar installation using Tactile™ Wall products. Not every designer or location requires vibrant glitz.

Visual Impact Technologies (VIT), USA [21], produces a range of stock diffraction grating tiles suitable for cladding and interior design applications.

The patterns and effects will be somewhat familiar but the fact that these products are being produced in robust materials (often glass laminates) means that the problem of scratching the surface of the gratings in heavy use applications, which often made these surfaces appear old and ‘less than sophisticated’, has been lessened. VIT’s stated mission is …"to provide alternative solutions to traditional glass and plastic utilization, while enhancing current applications with art and creativity to provide new visual experiences that combine light with technology [22]. This has involved some fairly large projects such as glass wall cladding for trade exhibitions as shown here on a construction for the Intel Corporation.

Because diffraction grating material can be ‘seen’ in multiple or diffused lighting situations, specifically directed lighting does not have to be installed, which can greatly reduce the cost of architectural installations and make these products useful for ‘casual’ usage in domestic or corporate environments. Details of many newly announced commercial products and services relevant to this area of design and manufacturing can be found in Holography News [23].

Steel and Light [24] , a Division of Tru-Form Metals, based in California, offer diffraction grating furniture which relies on just this ‘relaxed’ attitude to illuminating holography. In fact, the more light shining on these objects, the stronger the visual effect.

![]()

Glass top furniture is popular and to include holographic diffraction material within the glass is a logical step. These are purely visual effects incorporated into products which can be used to ‘decorate’ an environment, but the same idea of diffraction and tiling has been used by artists as a way of building larger scale objects and installations, while at the same time allowing them to ‘move’ or distort space and the objects which appear in those spaces.

"Light Chair 2000", produced by artist Pearl John [25] and students on one of the holography courses she teaches in the USA, contains 45 rectangular holograms. Not a mass producible commercial product, but an exploration in ways of placing ‘light’ (and the holography which stores it) in non-traditional display situations. Sitting on light (or the promise of being able to) and dimensional camouflage open up many possibilities for students to explore diffraction gratings, the production of holograms and ways to display them. This provides a method of linking art and science for students with little or no knowledge of contemporary art. As John comments in her paper on the subject, "Not only have students not previously heard of postmodernism, but they also have no opportunity to see contemporary art. They have had no exposure to installation and they are also introduced to the concept of public art."[26]

ON THE WALL

The opportunity to use holography for the incorporation of different spaces into sculptural and painted objects has attracted artists since the early days of the medium. One excellent example, by artists Rudie Berkhout and Ward Bos, shows how a painter (Bos) and holographer (Berkhout) can collaborate on a permanent commissioned installation used to enhance the space within a building. Unveiled in 2001 at the Bank of America Technology Center, Charlotte, USA, "Odyssey 2001" is a triptych of painted panels and 12 reflection holograms. Optical illusion (the shape and placement of the holograms and paintings) is used to enhance the impression of depth in this work, along with the actual three-dimensional space in the hologram sections and the multiple thin layers of paint on the canvases, which help to give an impression of "infinite depth".

Both the painted and holographic elements combine to form an integrated work, achieving a difficult balance, as holography almost always overwhelms other media it is placed with. Extensive details, and images, explaining the design and production of this installation, can be found on Berkhout’s web site. [27]

Artist Setsuko Ishii has worked on many commissions for public and private art installations where the incorporation into architectural spaces has been paramount. In this example she has mounted several rectangular holograms together for the entrance hall of a domestic residence.

The pieces show a more traditional approach to framing and can be likened to the extensive use of stained glass in turn-of-the-century European housing or the decorative tiles used in many art deco residences. Here, however, the light and colour exist not only within the holographic rectangles but also in the space between the viewer and the hologram surface. She has also worked on much larger public installations, as can be seen in this piece, using transmission holograms hung within a building void.

Karsten Habighorst [28], Germany, has completed several installations for architectural spaces. Here, for example, he has used transmission holography as part of the signage for a bank entrance in Beckum, Germany. This 2 x 2.7 meter encapsulated hologram, produced in 1998, uses ‘colour’ effects to draw attention to the entrance area in a way that neon lighting might have been used previously.

The potential of holograms used in open public spaces is immense, but used infrequently at the moment. Architects often like the idea but reject holography because it appears difficult to light or does not offer the expected three-dimensional effect they were expecting. These sorts of installations are often incorporated after the building has been constructed (add-ons), rather than during the original design period. This can, of course, be a challenging benefit for the artist or producer who receives the commission at some later date, and the results can be spectacular, but incorporating holographic elements at an early stage has the potential to produce revolutionary buildings.

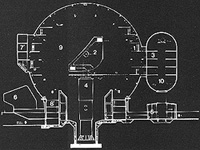

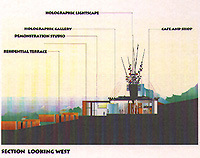

One project which did incorporate holography directly into the design of the building from the onset, rather than it being an afterthought bolted onto the outside, was the National Holography Centre, for a site in the East Midlands, UK [29] .

Architect Julian Marsh, along with artist Jo Fairfax, proposed a building which would not only include holographic walls within the structure of the project but an integral sculpture. The project did not succeed due to lack of funding but demonstrated how holography could be used intelligently as an integral part of the development of an architectural structure.

FLOORS AND ABOVE

Artists and designers are constantly exploring new areas to include holography and although hanging them in large public spaces, or using them to cover wall areas has proved popular, where we stand has drawn a lot of interest.

Over ten years ago, artist Vito Orazem collaborated with architects to produce holographic floor tiles which contain visual information (warnings or signs) for installation as optical barriers in subway stations. As a passenger approaches the gap between the platform and the track, the floor hologram would inform them, visually, to ‘stop’ [30] .

Although this use of holographic floor tiles was the result of a research project with the design department of the Krupps company, Essen, Orazem showed tiles for the first time in his exhibition at the European Media Arts Festival, Osnabrück, Germany (1988), and later they were installed in more public environments (discotheques and shops).

More recently, "Glass Ceiling", by artist Shu-Min Lin [31] demonstrates how holographic images can be used in a public environment (temporary gallery installations) and not only question the space we are walking in (or over), but also our perception of where images are displayed. The piece has been installed in several galleries (1996 - present) and adapts to the floor space available (sometimes 1000 square meters). There is no reason, however, why a such a dynamic installation should be confined to the temporary (and protected) display space of galleries.

One recent project, which moves this concept out of the refined atmosphere of a gallery and into a more public space, combines floor placement as well as hanging, mobile elements, is "Perpetuum Mobile" by artist Dieter Jung[32], installed in the European Patent Office, The Hague, Netherlands, in 2001. This includes a holographic floor area of 16 square meters with a 4.5 meter mobile structure hanging above.

The floor images are visible through 360 degrees and display different graphic colour images when viewed from different vantage points. This work differs from Min’s Glass Ceiling partly because it was a specific commission for a specific public space, but also in the content of the imagery and how viewers react to that imagery. Min’s faces can be threatening, particularly if the viewer walking over them is wearing a skirt. They are also ‘difficult’ to tread on as many people have an inherent dislike of treading on other people’s faces. Jung’s non-representational colour floor allows a greater opportunity to walk over it or stand on the light patterns without being ‘challenged’ by the content of the display. This, together with the mobile colour above, and the reflection of that structure in the glass floor below, provides a link between the two parts of the installation.

THE HOLOGRAPHIC PIXEL

Holography might be perceived, generally, as a 3-D recording and display system, but its ability to produce highly efficient colour effects in the form of diffraction gratings and holographic optical elements (HOE) has provided a new practical and visual channel for public and architectural installation. One of the leading organisations in this area is the Institute for Light and Building Technology (ILB), based in Cologne, Germany [33]. Headed by Prof. J. Gutjahr, this institute has been researching the use of HOE in architectural structures and demonstrated how specially produced holograms can be incorporated outside buildings to diffract daylight through the window and into the room beyond, thus reducing lighting costs and environmental pollution.

Part of the research has included the development of a computer-driven system capable of producing individual holographic pixels which can be recorded side by side to construct a much larger, and highly efficient, holographic (graphic) image. Colours can be specified during the production and several holograms can be mounted together to produce huge light installations. These pieces deal more with graphic, kinetic and colour effects, rather than recognisable three dimensional images and have been used in several large-scale architectural projects.

In December 1996 a massive holographic roof structure was unveiled on top of an electricity substation housed in the MediaPark, Cologne, Germany. The 150 square meters of holographic surface were designed by the Cologne artist Hingstmartin and produced using the holographic pixel system at the ILB.

Exposed to the elements, the holographic film surfaces are laminated between glass to protect them [34], and the diffractive colour effect can be seen from large distances. It was billed, at the time, as the world’s largest hologram.

More recently, artist Michael Bleyenberg [35] used the same pixel system to realise an entire wall for a new extension to the German Research Association’s (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) building in Bonn. "EyeFire/AugenFeuer" measures 13 x 5 meters and was unveiled in September 2000. Bleyenberg, a painter who learned holography as a student at the Academy of Media Arts Cologne, Germany, designed the wall to take advantage of the ILB’s pixel system, incorporating graphic designs and colour changes.

The resulting 26, 1 x 2.5 meter holographic sheets, on film, were encapsulated between glass and used to construct the side wall of the building. At night 6 search lights flood the holograms with light (3 from the roof of the conference centre opposite and 3 from the floor area directly in front of the wall). The effect is kinetic. The flat featureless wall disappears, replaced by intense shifting graphic images, patterns and colours. During the day ambient and direct sunlight bounces off the mirrored glass backing of each panel, travels through the thousands of tiny holograms and creates an ever changing pattern of colour. As observers move in front of the wall, their eyes will ‘pass through’ different parts of the spectrum generated by each holographic pixel. Bright sunlight produces intense spectral colours and subdued diffused light will create softer, more pastel colours. More details about the design and construction of this wall have been published in "This Side Up" magazine [36].

CONCLUSION

Holography as an architectural element is never going to live up to the expectations we place on it fast enough to satisfy our cravings for the three-dimensional spectacular. However, artists, designers and architects are beginning to have the opportunity to explore, in large-scale works, just what potential this medium offers. Some of the most successful works are those which have embraced the apparent failings of the technology, worked with them and produced innovative architectural, artistic and design installations. We still have a long way to go and now need planners and architectural practices who have the foresight and confidence to incorporate some of these possibilities into their projects. Taking the risk to expand the current boundaries of architectural and design holography can offer us spaces and structures we can celebrate.

Andrew Pepper

March 2002.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

I would like to thank the owners of images used in this paper for permission to reproduce them and to all those who have provided details about their work. Many thanks to Jonathan Ross for providing me with valuable research material and suggestions of where to look for diffraction and glass tile information.

[1] www.apepper.com, e-mail

[2] Dennis Gabor, A New Microscopic Principle, Nature, 161, pp 777-8. 1948.

[3] Holography at the Crossroads. An interview with the Father of Holography, Optical Spectra, Vol 4, part 9, pp 32-33, 1970.

[4] Light Fantastic, exhibition catalogue, Furst, Phillips, Wolf, Bergstrom + Boyle Books Ltd, London. 1977.

[5] A. Pepper, Beyond the Gallery Ghetto. The Creative Holography Index, The International Catalogue for Holography, Monand Press, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany, Vol 2, issue 2.

[6] See Sam Moree’s paper in the online version of this conference’s proceedings.

[7] A. Pepper, Windows with memories: Creative holography in the real world. This Side Up, No.10, June 2000, pp15-18. ISSN 1389 1707. Online version available at www.apepper.com

[8] See Jo Fairfax’s paper in the online version of this conference’s proceedings.

[9] Full details of this hologram and other work by Richardson can be found at www.holograms.uk.com

[10] www.holonorth.com

[11] E-mail to the author, from John Perry, March 2002

[12] MIT, spatial Imaging Group: http://spi.www.media.mit.edu/groups/spi/

[13] Several of these pieces have been shown in Germany. Details can be found on Vila’s web site www.vilamedia.com

[14] Harriet Casdin-Silver is represented by the NAGA Gallery: www.gallerynaga.com/current.htm

[15] Shown in Europe at the exhibition and conference ‘Holography 2000’, Austria.

[16] www.sallyweber.com Although this site currently features "Matrix", a non-holographic installation by Weber, other areas of her work will be included shortly.

[17] See (5).

[18] www.btagroup.com

[19] M. Crenshaw, Design Applications in Embossed Materials, Practical Holography X, SPIE proceedings, Vol. 2652, pp. 244-247, 1996.

[20] www.jbermanglass.com

[21] www.vitglass.com

[22] Stated on their web site, (see 21)

[23] Holography News, The International Business Newsletter of the Holography Industry, www.reconnaisance-int.com

[25] Pearl John launched a web site, containing details of her art work and educational activities to coincide with this conference: www.pearljohn.co.uk

[26] Pearl.V.John, Advanced Holography in High School, conference paper reproduced on her web site,(see 25).

[28] www.Visuell-Holo.de

[29] A. Pepper, The National Holographic Centre England: Proposal report. 6th International Symposium on Display Holography, Lake Forest College, Lake Forest, USA,SPIE proceedings Volume 358. Online version available at www.apepper.com

[30] Vito Orazem, Holography as an element of the media architecture, Fifth International Symposium on display Holography, Lake Forest college, SPIE proceedings Vol 2333, pp 168-177, 1994.

[31] www.shuminlin.com

[32] www.holonet.khm.de/Holographers/Jung_Dieter/text/MobileE.pdf

[33] www.ilb.fh-koeln.de

[34] www.dupont.com/safetyglass/lgn/stories/1007.html

[35] www.holonet.khm.de/eyefire

[36] A. Pepper, Building with Light: Holography, Glass and Architecture. This Side Up, No.15, September 2001, pp 2-4 ISSN 1389 1707. Online version available at www.apepper.com

| exhibits | gallery | writing | teaching | biography | contact |